by Eric Clow.

Self-care is a concept I have wrestled with for years. In writing this article, I tried to understand why I often find it difficult to take good care of myself. First, I scrutinized my parents, who always had high expectations of what I could do, which translated to “what I should do” in my mind. I considered the examples they set: my mother, who consistently made family her top priority, even when it impacted her own health and happiness; my stepfather, who wrapped up his sense of worth in large-scale projects to change the world and took notoriously terrible care of himself; my father, who’s struggled with alcoholism and setting appropriate boundaries with friends. Then I turned to myself, examining my own perfectionist streak, tendency to procrastinate, and bullish stubbornness.

My investigation also drew me to the attitudes I encountered from doctors and disability activists alike. The former dwelled on the downward trajectory of my muscles, which seemed most useful in teaching medical students the nature of neuromuscular disease. The latter offered something much more exciting, which I realize now is exactly what I wanted to hear: I didn’t need to be cured because my disability was part of who I was—a radical idea that I still believe. The problem? At the time I was seeking any excuse to protest the advice of doctors, who prescribed light exercise and stretches that promised only modest returns. And what better excuse could there have been for a rebellious disabled teen than “you’re fine the way you are; anyone who says different just wants you to be normal?”

Likely some combination of the above implanted the idea that caring for myself was somehow not important. Whatever the cause, the result was the same: I valued my disabled body less than my able mind, not realizing the two were linked. After several physical and emotional crashes strewn throughout college and the years beyond, I began my first forays into the world of self-care, though I didn’t call it that. Counseling gave me tools to work through stress and self-advocate. Music provided space to loosen up and process difficult emotions. But the most important practices—the ones that addressed my whole being—emerged only in the last few years and didn’t become routine until now.

Writing poetry, which I often do while sitting in my backyard, is one of my current self-care activities.If you’re like me, you may have initially written “self-care” off as indulgent, possibly even selfish. It’s a hashtag at the bottom of an Instagram post promoting some beauty product, or a distraction from the important work of social justice. There is truth in the critique that self-care has been exploited by commercial interests and facilitates an individualistic approach to structural problems that require collective action. But we aren’t tied to these distortions. We can reclaim what it’s meant to be.

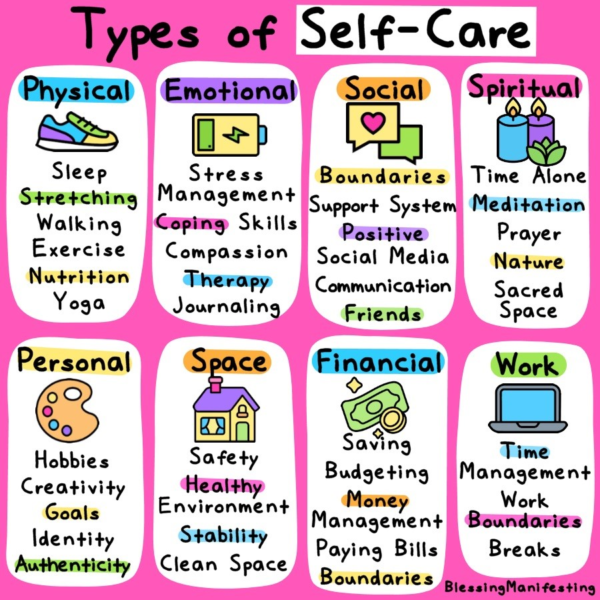

Self-care is typically defined as any activity you do to maintain or improve your physical, mental, and emotional well-being. These activities span the gamut from physical and emotional ones to social and spiritual, even extending into how you organize your personal space and manage your finances (see the graphic below from Blessing Manifesting). The logic is simple yet powerful: since only you know what makes you feel good and healthy, only you have the capacity to prioritize those practices.

Though anyone can benefit from practicing self-care, its most radical expressions manifest in communities of color and LGBTQ people, thanks to the groundbreaking work of Black Feminists like Audre Lorde. In “A Burst of Light”, Lorde equated self-care to a revolutionary act. She wrote, in discussing her battle with cancer, “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare.” Her ideas continue to resonate with writers and activists at the margins. For Evette Dionne, “self-care is a radical feminist act for Black women because we’ve spent generations in servitude to others.” Black trans advocate Devin-Norelle uses Instagram as a platform for public displays of self-care out of “resistance toward the forces that tell me that people like me shouldn’t be.”

Disabled people experience a distinct form of oppression that differs drastically in scope and origin from racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and others. Still, many of us are familiar with the varied ways society devalues the lives of those who challenge the “norm.” The refusal to provide access and accommodations, the denial of essential services, the lack of media representation, the implicit and explicit messages that we should not exist as we are—people with disabilities contend with these and more as we navigate a world that wasn’t designed for us. Reading the words of Audre Lorde, I realize that if I want to defy the society that says my body is worthless, I do that by demanding the care it deserves.

Today my self-care routines range from daily journaling and meditation to stretching and swimming (when the weather permits) to writing poetry and birding. I strive to substitute books, podcasts, and quiet in place of social media and TV. I say “no” to overexerting myself. When doctors dismiss changes to my condition as inane, I ask questions or get a second opinion. I am still learning the language my body speaks and grappling with what it needs, but I’m leagues beyond the teenager who decided his body didn’t matter.

This Saturday, December 12th from 1-2 PM, I look forward to delving further into the creative self-care activities I practice. Find more details on our event page here. In the meantime, you can ruminate on these questions to discover what self-care may mean to you:

- When and where do you feel most creative?

- What activities make you feel best (physically and psychologically healthy)?

- How can you prioritize these activities in your daily routine?

If you enjoyed this blog and would like to support Art Spark Texas, consider making a donation today.