by Eric Clow

Like many Americans, the COVID-19 pandemic that swept the globe instilled in me tremendous anxiety and uncertainty, and a sudden cancellation of nearly everything (including my wedding). Fears ranged from my susceptibility to severe health consequences if I contracted the virus, to worry for my friends and family members similarly vulnerable, to economic damages that would impact–and have impacted–many local businesses and organizations I love. My significant physical disability, paired with the limitations of those in my household, meant I had to depend on outside caregivers and trust they would take the physical distancing guidelines seriously. Further compounding my anxiety was the widespread scarcity of masks, sanitizers, cleaning supplies, and other essential items because of unnecessary panic buying. I prepared for the worst, but what I didn’t expect were the myriad ways this crisis would spark changes–for the better.

The same tools and technologies that enable non-disabled people to survive a pandemic allow disabled people to thrive in normal circumstances.

Once our overwhelming fears subsided, my fiancée and I, both limited by our very different disabilities, settled into the new normal of pandemic life: staying home as much as possible, avoiding all non-essential in-person meetings and events, using delivery services for groceries and other supplies, communicating with doctors electronically, and adapting therapies and exercise routines to our home environment. Then we opened space for the creative and social pursuits we had been missing. I exchanged poems via email with fellow writers, restarted a web comic collaboration with a talented visual artist, organized Netflix parties with friends. My fiancée moved her writing groups to Skype, enrolled in an online class, and taught a few of her own. Together we discovered online open mics where we could share our poetry.

It became apparent that we could do so much more without over-tiring ourselves than we could before the pandemic. Work meetings, classes, doctor appointments, social gatherings, art events–we might accomplish any or all over the course of a single day without depleting our energy for the next day; plus, the energy saved meant we could be more present and effective in each activity. As a bonus, the financial strain inflicted by COVID-19 prompted many performance venues, museums, festivals, and streaming platforms to make content available online at an affordable cost or even free. For many limited by fixed incomes, transportation difficulties, physical or cognitive abilities, this unprecedented access represented the opening of new worlds of art and entertainment.

None of this is to suggest that virtual experiences can ever truly compare with in-person ones, or that the unexpected perks enjoyed by a few can outweigh the suffering of many. It is to say, however, that these new options allow people previously excluded from an array of activities to participate, and to choose which activities they would rather give the bulk of their energy. Now that these accommodations exist and have proved useful, they should remain available to those they benefit. As the pandemic dissipates, we should expand and improve these methods, not cast them aside.

If we can make that accessible, why not this?

Though many disabled people have welcomed the recent proliferation of home-based alternatives for work and school, they have also expressed frustration that these same accommodations were frequently denied or deemed impossible before the pandemic. Now that educators and employers have successfully provided these modifications to people without disabilities, they should honor these requests from disabled people in the future. The same goes for communication services like ASL interpreting, which are often ramped up during emergencies but neglected at regular times.

Additionally, some in the disability community have begun to wonder, in what other areas might these accommodations be applicable? For example, could the same technology used to put museum exhibits online be repurposed to create a virtual tour of a historic building inaccessible to wheelchair users? Or, could crowded, standing-room-only music venues use captioned live streaming to include people with mobility limitations, chronic pain conditions, or sensory hypersensitivity from home? Perhaps live streamed events could also offer audio description. Or maybe the efficacy and convenience of telemedicine could translate to government agencies, helping people with disabilities and low income navigate rigorous eligibility applications and appointments.

As Andrew Pulrang explained in his recent blog article, these sorts of virtual accommodations “should never be treated as a substitute for community accessibility, accessible transportation, and community integration.” Still, they could serve as temporary solutions for businesses and organizations transitioning to full ADA compliance, or as Pulrang suggests, when an individual’s condition changes–a common occurrence among disabled people.

Essential workers are essential. So is art.

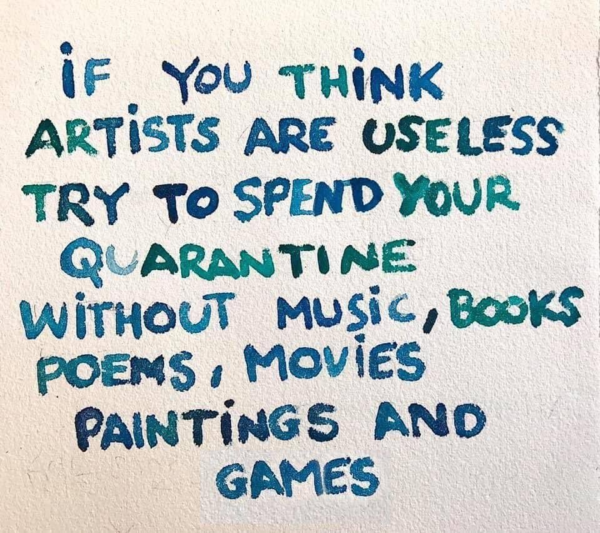

The glowing appreciation shown in recent months to healthcare professionals, grocery stockers, custodians, mail carriers, delivery people, garbage collectors, and others–the workers who hold up our infrastructure–has been deeply heartening. And though many are far from earning a rate commensurate with the service they provide, perhaps this newfound gratitude is a starting point for elevating the status of these roles. I see artists occupying a similar position. A meme currently circulating social media reads, “If you think artists are useless try to spend your quarantine without music, books, poems, movies, paintings and games” (see image below). Humor aside, I think it cuts to the core of why art matters. Art provides escape, enrichment, connection, relief. It lifts our spirits, challenges us to dream big and shift our perceptions. It can form the basis for a lifelong career, and the therapeutic outlet for someone coping with immense pain. Such an integral part of our lives should be nurtured in our children, taught in our schools, and most importantly, accessible to all regardless of ability.

A Different Path Forward

I know we are not out of the woods yet, not even close, but soon we will be. I hope that a return to normalcy does not entail a rapid forgetting of all the lessons this pandemic has taught us. Despite the tragic losses and devastating economic consequences, we have been granted a rare opportunity to envision a new way of living, one that prioritizes compassion to our most vulnerable, and appreciation to the essential workers that power our everyday lives; care for ourselves, our neighbors, and our environment; accommodations that make the world more accessible to people with disabilities and older adults. Undoubtedly there are many other changes we should carry with us or that we should implement to mitigate future health crises. I look forward to hearing more from our artists, officials, essential workers, and all of you on how we can strive for improvement, together. Maintaining these lessons will require constant effort, but sometimes a glimpse is all we need to forge a different path.

Eric Clow, [email protected]

Media and Communications Specialist

Art Spark Texas

Excellent and thought-provoking article. Thank you. I