The Many Lives of Jeffrey Moyer

by Eric Clow

You’d be hard-pressed to find an artist who embodies the spirit of Disability Pride Month more than Jeff Moyer. Now 74, Jeff saw a fledgling disability community transform into a well-organized civil rights movement. And more than that, he was a part of it. He worked with Ed Roberts at the first-ever independent living center. He sang outside the famous 504 sit-in. He witnessed the signing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), then played at a Senate reception celebrating its passage.

He’s also been a fierce advocate in his personal life. Jeff worked tirelessly so that his younger brother Mark, who experienced a severe cognitive disability, could enjoy a life in the community. It took decades, but Jeff was ultimately successful. In 2010, he donated a kidney to save the daughter of a friend—an act of selfless compassion that left him with serious chronic pain.

Jeff has assumed many roles throughout his life: singer, songwriter, historian, activist, author, educator, rehab specialist—and the list goes on. A blog article is ill-equipped to capture the breadth of such a multi-faceted man. But as I spoke with him, his artistry as a lyricist and writer soared to the forefront. I hope you’ll find his creative journey as compelling and fascinating as I do.

The Troubadour

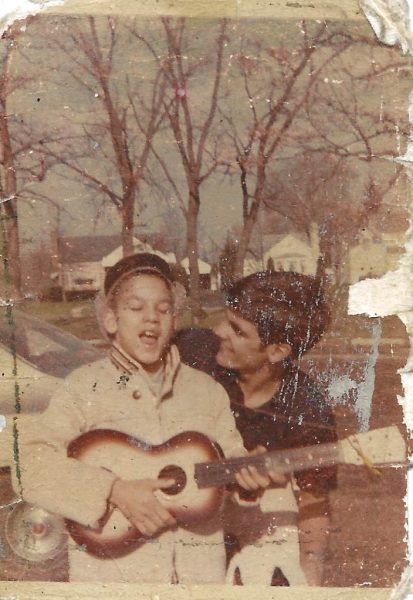

Jeff began to lose his vision when he was five. Because the cause wasn’t well-understood, many believed he was pretending. This sparked a great deal of confusion but also imparted the power of playing music by ear. “I was given piano lessons when I was six, but I couldn’t see the music and the piano teacher had been told I was pretending I couldn’t see. So he made me sit back as if I could see it. I wanted to play, so I’d imitate him and my mother would school me and teach me the song until I was playing it by memorization. And then I’d go back and perform it, and [the teacher] turned the pages as if I was learning to play.”

By the time he picked up the guitar at age 14, Jeff opted to teach himself. “I knew that I could hear chord changes, and if you can hear chord changes accurately, then even if you’re just strumming, any chordal instrument … is easy to play.” Jeff went on to learn 20 instruments, instructing himself along the way.

But perhaps his greatest teachers were the folk giants of the early 1960s. “People like Phil Ochs and Bob Dylan and Tom Paxton were probably the big three that I was listening to. And they were writing songs that said something and in chords that were easy to sing. It was all about the heart. And I fell in love with that.”

Inspired by these protest singers, Jeff penned his first lyrics when he was 15 years old. He continued to write one song each year, which he considered the minimum to be able to call himself a songwriter. But he became much more prolific when he started meditating in his 30s. “When I started getting connected to my spiritual source, instead of waiting for the muse to speak to me, I could go into the zone and pull a song out. And I wrote 60 songs in about three months in that very productive period.”

His songs aren’t merely inspired, however. They’re also crafted. “The craft of songwriting is about using words effectively and cleverly and sparely. [It’s] about editing and taking out anything that’s extraneous. And that’s true if you’re writing a short story or a memoir or a song.”

As I explored Jeff’s various albums, I was struck by both the diversity and specificity of his audiences. He’s written everything from disability rights anthems to children’s songs to an album for people in hospice care. I wondered how Jeff chose his audience. But it was actually the other way around: “my audience has found me.”

At one point scrambling to make a living, he considered working as an assembly presenter in schools. One performance led to another, and soon he was traveling around the country, performing in schools and keynoting education conferences. Music proved not only to be a powerful educational tool. It held the potential to make young people more accepting of disability, in themselves and others.

“I realized that there was no one writing music for young people where they heard disability in the music, where they could identify and say, ‘yeah, that’s me.’ And so I started doing that and I was working at a People First Conference in Michigan, and I was on my way up there and I was writing this song in my head, ‘we’re people, just people, people living our lives.’ So I’m singing on the stage and there are 150 adults with cognitive disabilities in the audience. And they said, ‘yeah, we’re people first. We’re singing the song. We’re going to get up on stage.’ And one by one, they pulled each other up on the stage until everybody was on the stage. What a great moment that was.”

Jeff’s foray into creating music for people in hospice was similarly fortuitous. “I started volunteering in hospice, which was what my heart was leading me to do. And I did 300 concerts in a big hospice center where people were dying and … got a lot of comfort through music. And I produced an album called Peace Sweet Peace.”

Jeff has written 600 songs and earned quite a following. But winning fans has never been his priority. “Our culture so adores success in its most grotesque form, like the superstar, that many people feel … if they can’t become that, then they fail. And the fact is, our successes are every interaction with another human being that is positive… We have to quit looking at a stage with adoring fans as success and look at any time we make someone else happy with our art.”

The Author

In the last 15 years, writing has taken precedence in Jeff’s life. The transition from music to this new art form was a matter of necessity. With increasing pain and limitations, Jeff couldn’t keep up with the demands of touring. “I used to do … three, four shows a day, and there’d be set up and breakdown and an hour show, very audience involving.”

Undeterred by this need to adapt, Jeff infused the same passion and work ethic into his writing. In 2016, he published his 400-page Grit: A Family Memoir on Adversity and Triumph. The book recounts his life as the Disability Rights Movement morphed into a powerful force for change. He’s also written a forthcoming short story collection called Underdogs: Heroic Stories.

Long-form memoir and short stories may seem like disparate mediums, but Jeff approaches them in a similar way. “I believe in writing short things. So, my memoir is 75 essays to tell one story… It’s a continuous story, but it’s told in small stories. And [it’s] the same with short stories, of course. You can have a quick story that has a lot of potential for thought.”

His books share more than this penchant for brevity. “I write about adversity. Because life is about adversity. Life is pain divided by moments of pleasure. Or you can look at it as pleasure divided by moments of pain, but you’re going to get both. And disability is a great teacher.”

Jeff writes on a Braille Touch keyboard with synthetic speech that reads back the text. He then sends his writing to his secretary, who edits any grammatical issues. “I believe in two pairs of eyes. And I also now use artificial intelligence. I have a piece of software that we run my writing through, and it helps me tighten [the writing], which is amazing. I’ve not used it in the creative process, but certainly in the editing.”

Jeff writes every day, dipping into poetry as well. “My main thing these days is, I write sonnets to people. I like the poetic form, the sonnet. It’s demanding. It takes some chops as a poet to write a sonnet that reads well. I like to lift up other people by giving them a sonnet about themselves.” Discussing this latest pursuit, Jeff offered perhaps the best encapsulation of his life’s work. “My job is to make other people feel good about themselves.”

Support the “Troubadour of Inclusion”

Jeff Moyer’s website is the best place to find his books, music, and other works not mentioned in this article. You can also stream many of his albums on platforms such as Amazon, Spotify, and Apple Music.

Or you can hear him speak and perform at our virtual Lion and Pirate Open Mic on Sunday, July 2nd at 1 PM Central or on the Art Spark Radio Hour on KOOP Hornsby-Austin on Monday, July 24th from 2 to 3 PM Central.